Before Ernest Cline’s “Ready Player One”, George Orwell’s “Ninteen Eighty-Four” and Aldous Huxley’s “Brave New World”, there was Yevgeni Zamyatin’s “We”, the first dystopian novel ever written. The book is a satire on life in a collectivist futuristic state, “One State”, located in the middle of a wild jungle. It is surrounded by a wall of glass and occupied by humans who live in buildings built of glass, have numeric names and wear identical uniforms. In Zamyatin’s plot, the ruler, the “Benefactor” with the assistance of the police force, the “Guardians”, directs the citizens of “One State” to undergo the “Great Operation”, which destroys the part of the brain controlling the imagination and passion.

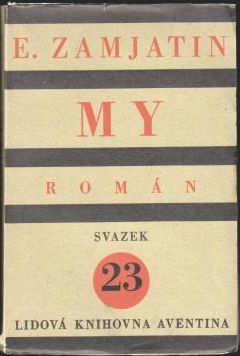

Despite the fact that the book’s content is fictional, it had the potential to be interpreted as having a hostile attitude towards the Marxist-Leninist world view, and therefore distribution was banned in Russia. The first English translation and true first edition of the novel was published in New York by E. P. Dutton in 1924. It wasn’t until 1927, that Russian editions began circulating outside Russia in Eastern Europe, having been translated back from the English, suffering severe alterations in the process 1. One particular edition that appeared in the Russian émigré journal “Volia Rossii,” caused an open political campaign against Zamyatin in the Soviet Union that led to his emigration to France in 1931. The book was not to be published in Russia until the glasnost era of 1988. Some of the 1927 Russian editions of the book are asking for $500 in on-line marketplaces.

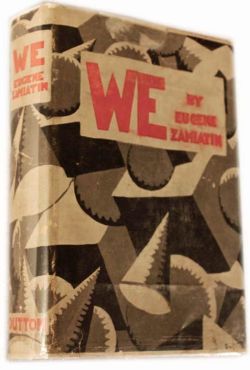

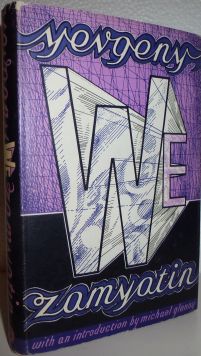

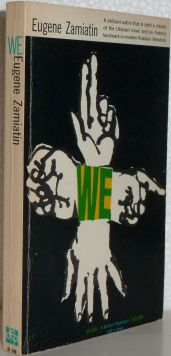

Copies of the 1924, E.P. Dutton American edition with a dust jacket are extremely scarce, commanding five figures. E.P Dutton reprinted the Gregory Zilboorg translated edition in paperback format in 1959 (paperback D39). Another collectible English edition is the 1970, Jonathan Cape London hardcover, which trades for about £250 in a nice dust-wrapper.

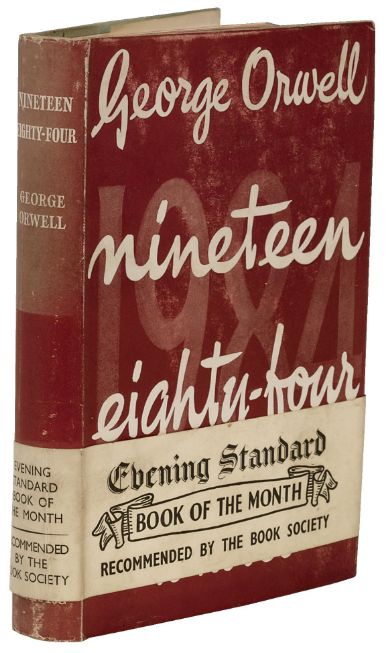

In June 1949, three years before George Orwell published his last novel Nineteen Eighty-Four, he reviewed “We” for the London Tribune readers. At that time, Orwell suggested that Zamyatin’s book was influential to the writing of Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World, and recommended it to readers as “in effect a study of the Machine.” It is also quite clear that Orwell borrowed some key components and characters from Zamyatin’s earlier book himself. Perhaps “We” deserves more recognition than it has had, but collectors are currently more excited about Orwell’s masterpiece. Fenwick2 records two variant states of the first edition dust-jacket, published in London by Secker & Warburg, one printed in green, the other in red. Complete copies carry the original wrap-around band, printed in black and are traded for more than $5,000. Orwell, who died the year after the release of his novel, had only signed a very limited number of copies, which are now extremely rare and highly sought-after.

One may argue that through a mix of creativity, plagiarism, and transmission of knowledge, works are almost never truly original. Robert Merton, in his book, On the Shoulders of Giants, digresses into the origin of Newton’s aphorism, “If I have seen further, it is by standing on the shoulders of giants.” With playfulness and a large dose of wit, Merton writes that Newton was already standing on the shoulders of George Herbert, who in 1651 wrote, “A dwarf on a giant’s shoulders sees farther of the two.” A generation before Herbert, Robert Burton, in 1621 wrote, “A dwarf standing on the shoulders of a giant may see farther than a giant himself.” Before him, with a similar aphorism, stood Spanish theologian, Diego de Estella, who got it from John of Salisbury in 1159, who copied Bernard of Chartres in 1130: “We are like dwarfs standing upon the shoulders of giants, and so able to see more and see farther than the ancients.”3

The theme of one man, living in a totalitarian society, constantly being watched by the dehumanizing forces of an omnipotent, omniscient, Big Brother, Benefactor, Mustapha Mond, The Capitol, etc., have political implications of official distortions. It is a warning against totalitarianism under any disguise, whether it parallels the activities of Cheka or those of America’s surveillance apparatus or the presentation of “alternative facts” by government officials. It is the theme that does not fall out of fashion; a major hit indeed. Editions of “Nineteen Eighty-Four” still occupy top spots in Amazon’s “movers & shakers” thanks to National Security activities. Outside the United States, in Britain and Australia, sales have risen by 20% so far this year compared to last year, according to Penguin Books. In the meantime, back in Russia, second-hand bookshops and science fiction in general are vanishing. Moscow is left with just six used bookshops compared to approximately 7,000 in Paris and detective stories are at the top of Russian bestseller lists.

——————————-

1 Olshanskaya, Natalia (2011). “Russian dystopia in exile: translating Zamiatin and Voinovich”. In Baer, Brian. Contexts, subtexts and pretexts: literary translation in Eastern Europe and Russia. John Benjamins Publishing. pp. 266. ISBN 9027287333.

2 Gillian Fenwick (June 1998). “George Orwell: A Bibliography” London: St. Pauls Bibliographies. A.12a. ISBN 978-1884718465.

3 Merton, Robert K. (1965) “On the Shoulders of Giants: A Shandean Postscript.” The Free Press, New York .

{ 3 comments… read them below or add one }

1826. Mary Shelley. “The Last Man.”

Thank you for this post. I read We in college and not only was it clear to me that Orwell lifted major themes from it in writing 1984, but that Zamyatin’s book is the better of the two.

Jack London’s, “The Iron Heel” was published in 1908. That’s my vote for first dystopian novel.

{ 2 trackbacks }