We recently had the opportunity to speak with Laurent Ferri, Curator of the pre-1800 Collections Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections, at Cornell University.

We recently had the opportunity to speak with Laurent Ferri, Curator of the pre-1800 Collections Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections, at Cornell University.

RBD: Within the scope of your definition of a book [“a closed/bound container of ideas and symbols which reflects and supports the intentions and worldview of its “author(s)”], what are some of the “rarest” books that you had the opportunity to examine?

FERRI: The distinction that most of us are making between “rare books” and “ordinary books” did not make sense during centuries: all medieval books were “rare” and, to a certain extent, “unique”. I like to tell the (certainly apocryphal) story of Saint Francis of Assisi who found a discarded or lost piece of parchment detached from a volume of sermons, lying in the mud, near a scriptorium: the saint took the time to stop, pick it up, and clean it up slowly and lovingly; he then told his companions that every book containing the word of God (the only Author) should be respected and preserved. By contrast, because people have quick access to millions of printed books, images of books, and e-books today, they become snooty or blasé.

In addition to the market value (supply, demand, and mimetic desire), there is obviously the number of existing copies; the condition; the provenance (I am just coming back from our vault, where I saw the sublime “Piranesi albums” given to the brother of the King of England by Pope Clement XIV.: you cannot beat that!); there’s also the difficulty to access and/or read the book; finally, there is the sentimental and/or religious value of the item.

Ernst Gombrich wrote, in the introduction of his “History of Art”, that there is no “good” or “bad” reason to like or dislike a cultural artifact: in that sense, it is difficult to say what “the rarest book” is, using only objective or universal standards. A lovely book that was given to me when I was a child, Gédéon en Afrique, is arguably “the rarest thing for me” — but not for anyone else!

But seriously – I may soon have a chance to examine “Les Très-Riches Heures du Duc de Berry” and, as you can imagine, I am very excited: the most beautiful book of hours in the world is also notoriously inaccessible! Another rare book I would like very much to see in Chantilly is the copy of Caesar annotated by Montaigne, with the manuscript note indicating that he read it “from February 25 to July 21, 1578”.

I could also mention the magnificent Dutch atlases of the 16th and 17th centuries; Chinese “jade books”; or the first edition of Whitman’s Leaves of Grass (1855), which I saw at the Beinecke, which is like Ali Baba’s cave.

Let’s try and say something more original: at Cornell, we have this unique bound manuscript called the Paidikion, which is probably “the rarest book on a high-risk subject” I’ve ever seen. It is made up of homoerotic stories, and contains a detailed listing of all the sexual encounters of a famous English linguist (1883-1957) who had a secret, scandalous life: he was attracted by very young men, and did more than just collecting the conventional erotic photographs of Wilhelm von Gloeden (some of which are inserted in the volume). There is a disturbing and awkward sense of voyeurism when you examine this diary, long thought to be lost, and which achieved a “mythical status” in some circles. If my memory doesn’t betray me, Gide mentions it in his correspondence. Anyway, passages of the Paidikion were eventually published in The International Journal of Greek Love [sic] in 1966. Today, it is made available in an academic library, “by appointment only”.

RBD: Excluding Cornell, which other institution has made a huge advancement in rare book special collections in recent years?

FERRI: Generally speaking, there is increasing global competition for “the best (rarest) stuff”, because institutions need to differentiate themselves from other “brands”. National libraries like the BnF or the British Library have this advantage over private universities or collectors that they can use preemption policies to block the export of “national treasures” and expand their century-old collections.

Philanthropy in the US remains spectacular: in February 2015, Princeton received a $300 million (!) gift of rare books from William Scheide, including the first six printed editions of the Bible, the four folios of Shakespeare, etc. Also, it is impressive to see new institutions building world-class collections of rare books and manuscripts “from scratch”: for example, the Aga Khan Museum in Toronto, which opened in 2014, can already boast the earliest surviving manuscript copy of Avicenna’s medical Canon, as well as marvelous Persian illuminated books, which even an institution like Cornell would never be able to acquire.

I must admit I am not aware of all the “advancements” made everywhere. Public shows are eye-openers. The most spectacular exhibitions of rare books are probably at the Morgan Library and Museum: I particularly enjoyed “Drawing Babar” (2008) and “Illuminating Fashion” (2011), both the physical exhibition and the web sites. Recently, “Aldo Manuzio: Il Rinascimento di Venezia” (2016) at the Accademia was a tour-de-force.

RBD: The acute insider’s view is that most of the rare books of the world had moved into the libraries of institutions during the second half of the last century. How did institutions adjust their focus since then?

FERRI: There is a certain fascination with big numbers (especially big $$), which I find annoying. Important acquisitions are not just about resources and logistics. It is about preserving and transmitting our cultural heritage in an intelligent, creative, stimulating, and inclusive manner.

RBD: Apart from the content of rare books there is no more intriguing question in the rare book world than “What is it worth?” Is this question relevant in the context of the institutional collection?

FERRI: You are right: the “price tag question” is usually irrelevant when we consider books at the collection-level. An important library collection is like a major/designated historic monument, it is “priceless”. The French politician who wanted to “sell Versailles” to fund Social Security was being silly.

RBD: What are the areas of present-day interest that institutions are lacking behind private collectors?

FERRI: What I can tell you is that we will always need very passionate, focused, obsessive collectors. They are not event-driven (it is sometimes difficult to plan anything on the long term when you work in a museum), and they are nor hampered by bureaucracy or political correctness. We share similar enemies: inflation, speculation, ignorance, and conformism.

RBD: What is Laurent’s trophy book?

RBD: What is Laurent’s trophy book?

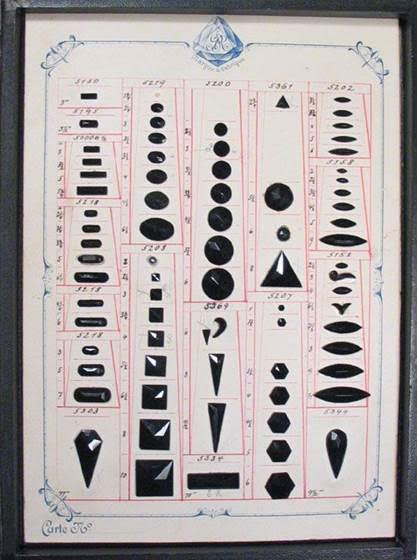

FERRI: It was fun to acquire a copy of Le Sorcier Noir by Jean Hérold and Gherasim Luca (1962), for our “Surrealism and Magic” exhibition at the Herbert F. Johnson Museum of Art, a few years ago. This trove manifests the Surrealist belief in the “magic potential” of the found object. It seems to have begun when Luca sent Hérold a playful collage of scientific images of different minerals. The result was a limited edition of fifty boxes, comprising fanciful texts by Luca; two states of an etching by Hérold; and a unique haberdasher’s sample card on which buttons found in a flea-market were affixed like specimens of rare gems, lending the whole an aura of mystery and arcane learning.

By definition, however, “the book of my dreams” I don’t have yet. So, let’s make a wish: it would be fantastic to acquire at least one volume from the Pillone Library, with a splendid fore-edge painted by Cesare Vecellio (1530-1601), a cousin and pupil of Titian: the volume showing Erasmus at his desk, maybe? Erasmus of Rotterdam is one of my heroes. I just finished reading his Epigrammata, in a 1518 edition, as well as his biography by Stefan Zweig, in the Kindle edition.

{ 0 comments… add one now }