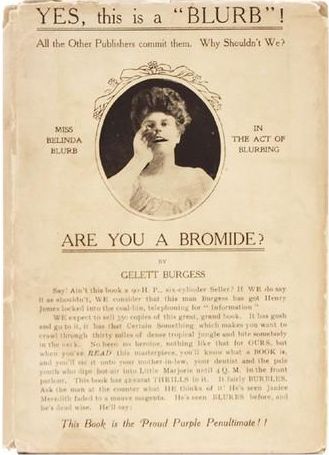

In 1906, an American humorist by the name of Gelett Burgess authored the book “Are You a Bromide?” On the back of its dust jacket the book featured a picture of a young, fictional woman Miss Belinda Blurb, in the act of blurbing – “YES, this is a ‘BLURB’!” And so the term “blurb” was coined. The pithy quotes from fellow authors, the short summaries of targeted judgments, the promotional pieces with or without pictures, are all part of what is referred to as blurb.

Today, blurbs are used more than ever before because more books are being published every year, and they offer an inexpensive way to distinguish and make a good first impression. As the printed book publishing industry keeps losing sales to electronic devices, the exterior of the printed book transforms itself into an attractive display, which seeks book buyers’ attention.

In the world of rare books, the blurb serves another purpose through the distinctively unique properties of a collectible edition. It is often used to correctly identify First Impression and First State dust jackets, in addition to any copyright, imprint and content designations. There are numerous examples where such verification is used. The following are some examples:

- In James Joyce’s first novel “A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man,” a blurb appearing on the upper panel of the first printing of the dust jacket that describes the book at odds with what the book itself was doing, was removed from later printings which carry a blurb by H.G. Wells.

- “Casino Royale” – 1st Edition/1st Impression contains a pencil drawing of Ian Fleming by Bartlett, with a blurb about Fleming’s life directly below.

- In “Tender is the Night” by F. Scott Fitzgerald, the original first issue dust jacket has the blurbs by Eliot, Mencken and Rosenfeld printed on the front flap.

- In the “The Lord of the Rings,” the correct first UK edition, first impression and first state dust jacket should lack any blurbs on the rear flap.

- In Maurice Sendak’s “Where the Wild Things Are,” first issue primacy is established through the text of the blurb which makes no mention of the Caldecott Award bestowed upon the book on publication. The winning of such a prestigious prize compelled the publishers to recall the entire edition and change the text on the dust wrapper to include the achievement.

- Ken Kesey’s “One Flew over the Cuckoo’s Nest,” first issue carries a blurb by Kerouac.

- Harper Lee’s “To Kill a Mockingbird,” first issue’s dust jacket bears a Jonathan Daniels quote and Capote blurb in green.

Such collectible treasures relied on blurbs to attract buyers and to serve as one of the most effective promotional displays. The end goal for every publisher, author, and bookseller was then as it is today – use anything that helps curate content. Today, however, a blurb on the back cover of a book is not as effective as a tweet or “electronic blurb.” In fact, Twitter, the company that invented the microblogging of short, targeted judgments, went public yesterday in a New York Stock Exchange frenzy that drove the seven-year-old company’s value to more than $25 billion and evoked comparisons to the dot-com bubble. With 231.7 million active users per month, an effective tweet can by far surpass the impact of a blurb.

A future with more tweets and less blurbs, and even less printed books, is already taking shape for books. Consider, for a moment, the probable effect of the publisher of “Where the Wild Things Are” tweeting instead of recalling the first issue of the book in order to add the important blurb of the Caldecott Award. The result would have been a lot more copies floating around with prices for the first issue being much lower. While the end of the blurb may be coming soon if publishers’ marketing strategies adopt the technology alternative, one thing for sure is that rare books with an important blurb will become even more attractive to collectors as blurbs become a thing of the past.

{ 0 comments… add one now }

{ 2 trackbacks }