When was the last time you were in the market for a fine binding? Did the presence of attractive marbled boards or marbled endpapers drive your purchasing decision? If you are like the majority of fine binding book collectors, marbled boards are probably an aesthetic bonus, but they do not constitute the driving factor behind your purchase. Most of the collectors and trade professionals simply do not have enough knowledge about marbled paper to justify paying a premium for it. In fact, the differentiation between marbled paper qualities and options is a task that is mostly reserved for the experts in the field which specializes in fine bindings and fine printing.

In recent decades there has been a worldwide revival of interest in marbling among artists, some of whom dove deeper into the old bookbinding trade for answers to questions such as date, country or marble of origin. The vast color variation and intermixture of designs have amalgamated to further frustrate the identification or classification of the marble. Since none of these designs come signed or referenced in any kind of blurb credit, the identification basis is the history of the trade. A brief history of the origins of the craft is necessary to help to better understand and value the art of marbled paper.

Marbling Master Charles Woolnought defined marbling as:

“An art which consists in the production of certain patterns and effects, by means of colors so prepared as to float upon a preparation of mucilaginous liquid, possessing certain antagonistic properties to the colors prepared for the purpose, and which colors when so prepared, floated and formed into patterns upon the surface of the liquid, are taken off by laying thereon a piece or sheet of paper, or dipping therein the smoothly cut edges of a book.”

The craft as we know it today first became known to European travelers in Turkey, Persia and the adjacent regions of the Near East after the middle of the sixteenth century. Libraries preserve many manuscript books and albums containing marbled papers of Turkish and Persian origin that can be dated to the late sixteenth century. Manuscripts known as Album Amicorum, Stammbuch in German or Livre d’amis in French, became popular with students who were using them as genealogical albums, and were frequently decorated with marvelous colored papers from travels to places where the trade was practiced.

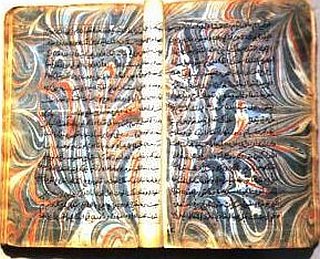

Literary record with existing specimens show that the Chinese made marbled papers at least three to five hundred years earlier than the Persians. Also, Japanese leaflets such as Poetical Works of Thirty-Six Men, published in 1118, contain sheets of suminagashi paper that may have originated from China. Suminagashi marbling consisted of layers of thin rings of black or blue color let on clear water, and manipulated into wavy patterns with a stylus or human hair before taken off onto paper.

Besides the pattern that a marble produces, the paper used is a key component in identifying and categorizing the work. In Turkey for example, the use of Ebru paper (originated from the term “ab-ru” meaning water surface) , was commonly used to ensure protection against forgery of the patterns they developed. In more recent times cheap machine papers imported from Europe replaced the material of the crafty marblers of Instambul.

Around the beginning of the 17th century, the craft was introduced in Europe, Germany in particular, marking the beginning of the reliance on imports from Persia or Turkey. Big industries were turning marble paper into a staple in the bookbinder’s shop. Further, the introduction of the art into the region coincided with the golden age of French bookbinding. The French were the first in Europe to use marbled endpapers, which are marbled papers cut up and pasted onto binder’s boards to serve as cover papers and decorations. This often meant marbled papers were used for decorating bindings made for people who had similar needs as those looking for wallpaper decoration. Fortunately , the nineteenth century brought a change in French marbling, as the industry was introduced to a Turkish pattern containing an infusion of turpentine to explode the effect of the color and give the appearance of a network of fine lacy holes. The use of marbled paper in German bookbinding did not occur until about the middle of the seventeenth century.

Charles M. Adams published the first detailed study of seventeenth-century European paper marbling in 1947. He pointed out that the diary of Samuel Sewall of Boston, a judge at the Salem witchcraft trials of 1692, contains references in 1683 and 1685 to having his books stitched in marbled paper. This paper, which found its way into England by way of Holland, was imported to American bookbinders from Amsterdam starting around the end of the seventeenth century. It was the well-known German marbled pattern that is now referred to as Dutch paper.

Marbling was one of the chief means available for producing the colored papers used in bookbinding, up until the changes brought by the Industrial Revolution in the nineteenth century, which caused the diminution in hand bookbinding and the extinction of the marbler’s art. Today hundreds of thousands of bookbindings decorated with marbled paper survive in European and American libraries, as wellas in the libraries of individual collectors.

{ 0 comments… add one now }

{ 3 trackbacks }