How fortunate native English-speaking booksellers are to have English as their mother tongue! English is the lingua franca of global business. Not surprisingly, the official language of ILAB, (The International League of Antiquarian Booksellers), is English. However, the organization maintains that this stature is shared equally with French; hence the old ILAB motto “Amor librorum nos unit,” translated “The love of books unites us.” British members volunteered a one letter adjustment to the term: “Amor librarum nos unit,” translated “The love of sterling pounds unites us!” A rather comical adjustment, since the European Monetary Union, and the Euro, or even the US dollar, are more appropriate currencies to unify ILAB.

How fortunate native English-speaking booksellers are to have English as their mother tongue! English is the lingua franca of global business. Not surprisingly, the official language of ILAB, (The International League of Antiquarian Booksellers), is English. However, the organization maintains that this stature is shared equally with French; hence the old ILAB motto “Amor librorum nos unit,” translated “The love of books unites us.” British members volunteered a one letter adjustment to the term: “Amor librarum nos unit,” translated “The love of sterling pounds unites us!” A rather comical adjustment, since the European Monetary Union, and the Euro, or even the US dollar, are more appropriate currencies to unify ILAB.

Modern first editions in modern foreign languages are not in as high demand as some of their corresponding English text translations. Abebooks, the premier on-line marketplace for rare books with operations around the world and six international websites, in English, French, German, Italian and Spanish, occasionally scores 20th century, foreign-language editions in its top sellers. In fact, a number of foreign language written novels, become more appealing to collectors once translated into English. Why is that? The world has a well-balanced distribution of important authors and volumes across boundaries and nationalities, of course!

It is more difficult to comprehend ideas and concepts if there are no words for them in one’s language. English, unlike Arabic or French, has no official language police to monitor the development of newly invented words added in the vocabulary. The problem is that the actions of the official language bodies tend to lag, as new scientific discoveries are made and new technologies and concepts developed, so that writers in these languages are seemingly put into linguistic straitjackets and time warps. A language that originally disallowed use of words not found in the Koran, does not offer the vernacular vocabulary or the repulsive language to express the “blast-furnace” images that made a novel such as Selby’s “Last Exit to Brooklyn”, a masterpiece in modern literature.

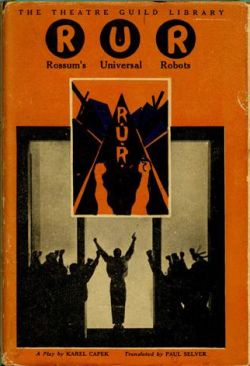

A rare book is worth what a buyer is willing to pay to own it. Naturally, what a buyer is willing to spend on the first edition of a book depends on her wealth. Even though English is only the primary language for about 5 percent (approximately 350 million of the world’s people), the top 20 wealthiest countries on a per capita income basis are almost all English-speaking or use some other Germanic language, with the exception of France, Japan, and Finland. Franz Kafka, a nonperson in Czechoslovakia during much of the Communist period, wrote in German (considered a ”world” language), and so his work was spared the fate of his Czech-speaking countrymen. Karel Capek, who wrote in Czech, had his work effectively banned during four decades of Communist rule. He received fame when his play, R.U.R. (Rossum’s Universal Robots), which coined the word “Robot” (deriving it from the Czech “robota”, forced labor), was translated into English in 1923.

Another argument is that collectors of fine and rare books consider dust-jackets an indispensable part of the book. More specifically, collectors of first editions would scarcely consider purchasing a volume that had lost its dust-jacket as issued. In Europe during the last century, book covers were published with simple images and plain type, often jacketless, because literary fiction is an easier sell in mainland Europe than in the UK or the US. Publishers there can be less overt in their attempts to grab the attention of customers, while cutting costs at the same time. Black-and-white German editions or plain wraps in French editions were very common, while the UK and US publishers employed designers to create striking dust covers. The UK book market is more competitive; all the covers in shops have to shout: ‘Buy me!’ In the US, meanwhile, publishers tend to signpost literary fiction more than the UK, because of even stiffer competition.

Still, texts in ancient foreign languages remain in demand. Classics, which are often studied in the original Latin and Greek, with horrific complexities of grammar such as gender, verb-endings, adjectival agreement, subjectives, and so forth, are very scarce in original editions. After all, the most expensive book ever traded is a 72 page journal, The Codex Leicester, with the scientific writings of Leonardo Da Vinci, in Italian.

{ 0 comments… add one now }