Times have changed and so have women, but not their innate ability to charm. Women possess the power to please or attract with their personality or beauty. Imagine living in another time, and, if it were to be the twentieth century, you would perhaps choose the hay-day of the 1920’s. It was a time for women to release femininity from trappings such as the corset and long, elaborately arranged hair, often kept under cover. Bobbed hair stood for an intriguing concept: feminine freedom whose participants became thrill-seeking adventurers, who, according to F. Scott Fitzgerald: “have a talent for living.” It was the Jazz Age mixed in with the imagination of Dadaism, Surrealism and Art Deco. Skinny was in, and many young women took to extreme dieting for leaner bodies in racy chemises. It was a time when the world shifted to a more overtly feminine direction.

Times have changed and so have women, but not their innate ability to charm. Women possess the power to please or attract with their personality or beauty. Imagine living in another time, and, if it were to be the twentieth century, you would perhaps choose the hay-day of the 1920’s. It was a time for women to release femininity from trappings such as the corset and long, elaborately arranged hair, often kept under cover. Bobbed hair stood for an intriguing concept: feminine freedom whose participants became thrill-seeking adventurers, who, according to F. Scott Fitzgerald: “have a talent for living.” It was the Jazz Age mixed in with the imagination of Dadaism, Surrealism and Art Deco. Skinny was in, and many young women took to extreme dieting for leaner bodies in racy chemises. It was a time when the world shifted to a more overtly feminine direction.

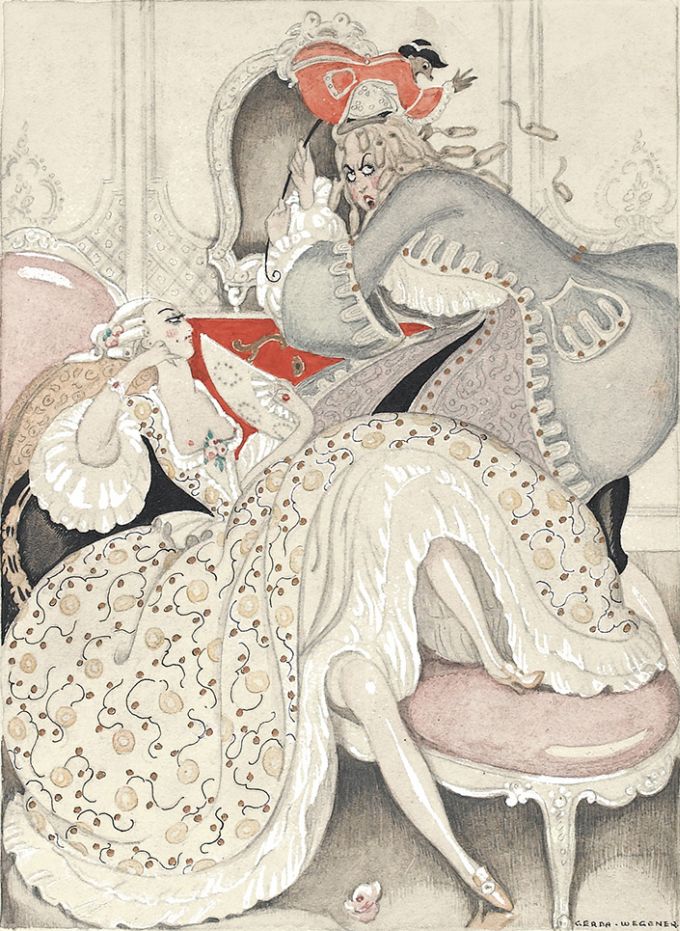

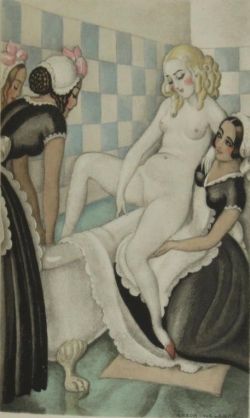

It was also the time when Gerda Wegener became famous. Beginning with projects to produce illustrations for La Vie Parisienne, Le Rire and La Baïonnette, she drew figures of young ladies using pastel color-palettes to evoke girlish charm in her subjects and give them a glow of femininity. Gerda’s sensual images of eroticism left little to the imagination. Her playful nudes, including graphic illustrations in the memoirs of Casanova, were celebrated throughout liberal society for their groundbreaking ploy of depicting female sexual pleasure. But even her most shocking nudes – explicit, almost pornographic, were well received at the time, because they preserved a cherub-like innocence that kept them from vulgarity. It came as no surprise, when at the most important art exhibition of the era, the World’s fair in Paris in 1925, she won two gold medals and one bronze for her work.

Her works published in book form are quite scarce but still relatively undervalued. “L’Anneau ou La Jeune Fille Imprudente” by Louis de Robert and “Amour Etrusque” by J.-H. Rosny aîné are two of the undated early works, published when she was less known. The latter contains 30 black illustrations in text and a color illustration on the cover. In 1918, she illustrated “L’Abdication de Ris-Orangis” by Léo Larguier for Édition Française Illustrée. It contains six full page drawings in black. The following year, the same publisher published “Contes de mon Père le Jars” by Eric Allatini, which contains twelve colorful illustrations set in delicate printed frames. The edition is limited to 650 copies, 100 of which are printed on hollande verge tiente and another 60 on japon. Her collaboration with Eric Allatini and G. Briffault produced “Sur Talons Rouges,” in 1929. The book has a frontispiece engraved in colors and 12 etchings in color. These works are quite scarce.

Gerda’s most appreciated work which was produced in the middle of her career, is also the most sensually explicit. One of these most spectacular artworks came from the commission made in 1925 by the French polygraph, Louis Perceau: twelve watercolors of high erotic and lesbian content, illustrated the 350 copies of his book: “Les Délassements d’Eros.” These paintings made her one of the most recognized erotic illustrators of all time. Her next work in 1927, was “Une Aventure d’Amour à Venise” by Giacomo Casanova, published in Paris for Le Livre du Bibliophile by Georges Briffaut. Gerda’s original watercolors were wood-engraved by G. Aubert and embellished in color by master engraver André Lambert. The edition was limited to 500 copies, of which 25 included 2 illustrations in black and yellow preparatory states, bringing the total to 10 illustrations instead of just the 8 aquatint printed plates. The following year, Georges Briffault published 2 volumes which included her work, titled “Les Contes,” and again in 1934, Briffaut published “Fortunio” written by Théophile Gautier. The book has 16 erotic colored etchings by Gerda, compiled in an edition of 392 copies printed on velin rives. The same book published by the same publisher in larger volume was illustrated by Paul-Emile Bécat. Collectors, however, have shown a preference for Gerda’s “Fortunio” illustrations which are now extremely scarce.

Gerda knew that to be a ‘real woman’ one must be beautiful and act in a feminine way. She was also quite aware that ‘femininity’ is performed, polished with makeup, mascara eyes, feminine lashes; exhibited with hairless legs, or in a uniform such as a prom dress, or a wedding gown. While, she herself, a woman of elusive power swathed in femininity, lived in Paris with her lover and model, Lili Elbe, who was previously her husband Einar. While technically married, Gerda and Lili lived as a lesbian couple after Einar’s sex reassignment surgery. Their story is portrayed in the film The Danish Girl. At a time when transgender issues are increasingly part of the wider culture, it’s vital to acknowledge the impact that Gerda’s art had in forging a path towards tolerance and acceptance.

{ 0 comments… add one now }