Modernism in architecture grew from the Bauhaus, a German architecture and design school established in 1919, in Weimar, by German architect Walter Adolph Georg Gropius (18 May 1883 – 5 July 1969). Paradoxically, Bauhaus, directly translated: “building house”, did not offer courses in architecture in its early years of operation despite a proclamation in its manifesto: “…the aim of all creative activity is building.” It was not until 1927, two years after moving to its new location in Dessau, that it began teaching architecture. Within six years of its founding, the Bauhaus style became one of the most influential currents in Modernist Architecture.

Gropius designed the new school and student dormitories at Dessau, in the new, purely functional, modernist style in which he was promoting. The school brought together modernists in all fields, featuring in its faculty, the modernist painters Vasily Kandinsky, Joseph Albers and Paul Klee, as well as the designer Marcel Breuer. Gropius served as the director of the school through the first year of its architectural operation. Under his direction, a very collectible magazine called Bauhaus was issued between the years 1926 and 1931, and a series of 14 books called “Bauhausbücher” were published 1925-1930.

1. Walter Gropius (ed.), Internationale Architektur, Munich: Albert Langen, 1925, 111 pp.

2. Paul Klee, Pädagogisches Skizzenbuch, Munich: Albert Langen, 1925, 50 pp.

3. Adolf Meyer (ed.), Ein Versuchshaus des Bauhauses in Weimar, Munich: Albert Langen, 1925, 78 pp.

4. Die Bühne am Bauhaus, Munich: Albert Langen, 1925, 84 pp.

5. Piet Mondrian, Neue Gestaltung, Neoplastizimus, Nieuwe Beelding, Munich: Albert Langen, 1925, 66 pp.

6. Theo van Doesburg, Grundbegriffe der neuen gestaltenden Kunst, Munich: Albert Langen, 1925, 66 pp.

7. Walter Gropius (ed.), Neue Arbeiten der Bauhauswerkstäffen, Munich: Albert Langen, 1925, 115 pp.

8. L. Moholy-Nagy, Malerei, Fotografie, Film, Munich: Albert Langen, 1925, 115 pp.

9. Kandinsky, Punkt und Linie zu Fläche: Beitrag zur Analyse der malerischen Elemente, Munich: Albert Langen, 1926, 190 pp.

10. J.J.P. Oud, Holländische Architektur, Munich: Albert Langen, 1926, 107 pp.

11. Kasimir Malewitsch, Die gegenstandslose Welt, Munich: Albert Langen, 1927, 104 pp.

12. Walter Gropius, Bauhausbauten Dessau, Munich: Albert Langen, 1930, 221 pp.

13. Albert Gleizes, Kubismus, Munich: Albert Langen, 1928, 101 pp.

14. László Moholy-Nagy, Von Material zu Architektur, Munich: Albert Langen, 1929, 241 pp.

An incomplete set of the “Bauhausbücher” sold for 15,000 Euro at the Christie’s auction: “Les Collections du Château de Gourdon,” held in Paris in 2011. The “Bauhausbücher” editions numbered 1, 2,4,5,8 and 14 have been re-issued in 2019 on the 100th anniversary of the formation of the Bauhaus.

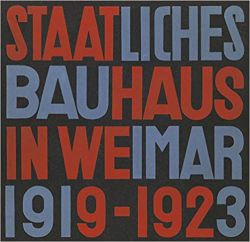

Gropius became an important theorist of modernism. He was an advocate of standardization in architecture, which developed into the mass construction of rationally designed apartment blocks for factory workers. His famous Bauhaus Manifesto, “Staatliches Bauhaus Weimar, 1919-1923,” Weimar and Munich: Bauhausverlag, 1923, 225 pp.,” issued in an edition of 2000 copies on the occasion of the Bauhaus exhibition, was re-released last year on the 100th anniversary of the school’s formation. When he left the school in 1928, he was commissioned by the Siemens Company to build apartments for workers in the suburbs of Berlin.

Swiss architect, Hannes Meyer became director when Gropius resigned in February of 1928, and brought the Bauhaus on a new track with a focus on reducing costs and becoming profitable. His two most significant building commissions, of which both still exist, are: the five apartment buildings in the city of Dessau, and the Bundesschule des Allgemeinen Deutschen Gewerkschaftsbundes (ADGB Trade Union School) in Bernau bei Berlin. These projects helped the school turn profitable for the first time in 1929. The change however, may have come at the expense of the school’s innovation and advancement in architecture, with a new functionalist approach considered by many political views to have leaned towards Communism. Under political pressure, Meyer was forced to resign in 1930.

Starting in 1930, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, served as the last director of the faltering Bauhaus, at the request of Walter Gropius. In 1932, when the Nazis came to power in Germany, they viewed the Bauhaus as a training ground for communists and closed the state-supported school. Mies decided to move operations from the campus in Dessau, to an abandoned telephone factory in Berlin and carry out a commission for Philip Johnson’s New York apartment. By 1933, however, the continued operation of the school was untenable and in July of that year, Mies and the faculty voted to close the Bauhaus amid Nazi rejections about the lack of “German” character.

Gropius left Germany and went to England, then to the United States, where he and Marcel Breuer both joined the faculty of the Harvard Graduate School of Design, and became the teachers of a generation of American postwar architects. In 1937 Mies van der Rohe also moved to the United States and became one of the most famous designers of postwar American skyscrapers.

{ 0 comments… add one now }

{ 1 trackback }