Two rare photography books portray two separate images of the beautiful city of Paris. The books represent the improbable encounter of two Parisian worlds: the surrealistic vision of Brassaï, and the documentary view of Atget.

Two rare photography books portray two separate images of the beautiful city of Paris. The books represent the improbable encounter of two Parisian worlds: the surrealistic vision of Brassaï, and the documentary view of Atget.

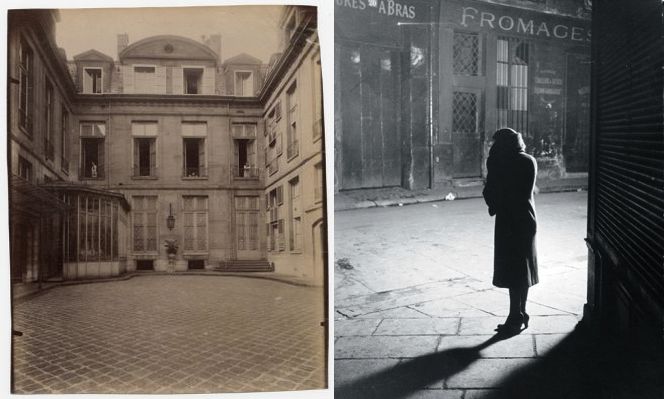

Eugene Atget (1857-1927), documented much of the architecture and street scenes of Paris before their disappearance to modernization. Most of his photographs were first published by Berenice Abbott after his death, in his book “Atget Photographe de Paris.” The book was published in 1930 simultaneously by Verlag Henri Jonquieres, in Paris and Leipzig, with the German edition, “Lichtbilder” which was released in a limited edition of 1000. The book captures Paris before its rapid changes; many of the areas Atget photographed were soon to be razed as part of massive urbanization

projects. It features photogravures of many of the areas and architectural locations in nineteenth-century Paris and Versailles with curiously empty streets, markets and shops, and objects that filled the discreet spaces in-between.

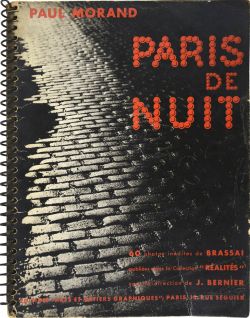

Photographs of Paris, by Hungarian born Brassaï (Gyula Halasz) (1894-1984), were published in the 1930s by Charles Peignot, director at Arts et Métiers Graphiques in a collection named “Paris de Nuit.” Paris by Night, Brassai’s first book, is a landmark work of technical achievement, with 62 pictures among the hundreds of nocturnal photos taken by Brassaï during 1930 and 1931. The images show an incomparably rich palette of blacks and shades of gray, with breadth of tonal range and exquisite expressiveness as light reflects in wet streets and diffused by fog.

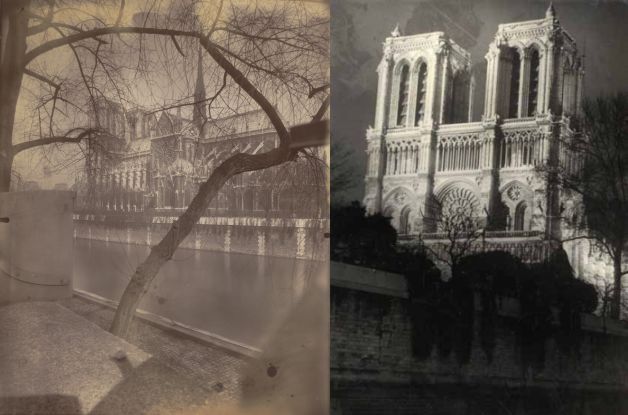

Brassaï : Notre-Dame La NuitMedium: Sheet-fed GravurePrinting

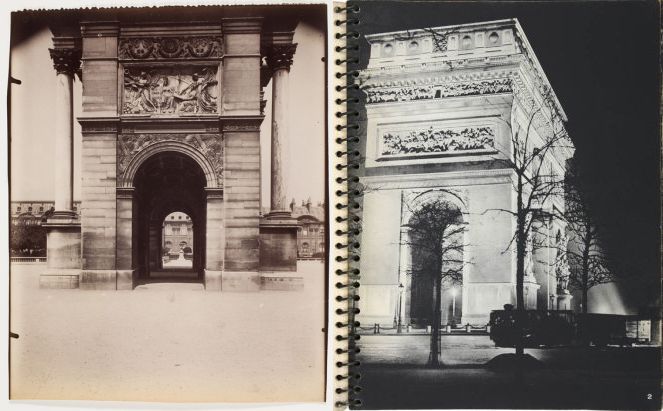

Atget’s photographs were taken with wide views at dawn, to give a sense of space and ambience. The first hour of light after sunrise, part of what photographers call the “golden hour”, or the “magic hour”, is the type of light which produces less contrast, reducing exposure to strong shadows or blown-out highlights. In Brassaï’s images, artificial light has come to replace that of the sun taken with a tripod and a long exposure time during the photographer’s long strolls after dark. The city looked as if bathed in artificial light, rendering a beautiful décor of transformed trees at the banks of the Seine mixed in with objects, which occasionally rendered disturbing figures.

A feature of shooting during the golden hour of the morning is that there are generally fewer people around at dawn than there are at other times of the day. Atget’s pictures of deserted streets, stairways, and shop windows show a subtle perception without much street life. Brassaï on the other hand, who became interested in photography as a way to record encounters on his nightly walks through the streets of Paris, captured the luminosity and the eeriness of all corners of the city and lifestyles of Paris at night in the early 1930s. His subjects seemed not only aware of the photographer, but they seemed to collaborate with him.

Both Brassai and Atget were two of the most influential photographers of the 20th century. Brassai’s unique style gave Paris de Nuit its distinctive intimacy and was a revelation for his artist friends. Surrealists Man Ray, Henri Matisse, and Pablo Picasso admired his work. Fellow night owl Henry Miller wrote: “Brassaï is a living eye…his gaze pierces straight to the heart of truths in everything.” Atget will be remembered in Bernice Abbot’s words: “as an urbanist historian, a genuine romanticist, a lover of Paris.” In 1931, four years after his death, the American photographer Ansel Adams wrote, “The Atget prints are direct and emotionally clean records of a rare and subtle perception, and represent perhaps the earliest expression of true photographic art.”

As officials are in a race to return Notre Dame to its former glory, the importance of Brassaï and Atget’s photography is reiterated. Their photographs are not only reminiscent of a city in its past beauty, but they also captured images using techniques and tools from a different period. Modern photographers, often work without a tripod, guerilla style, shooting hundreds of photographs a day which they then review on a computer screen and select the few to ultimately preserve, treating the city architecture as context-less two-dimensional abstract art.

{ 0 comments… add one now }